Dear All (and with thanks to Patricia Bradford for taking the lead on this newsletter):

Today, this paper in Nature takes us on a trip to the land of unintended consequences:

- Turner, A.M., Li, L., Monk, I.R. et al. Rifaximin prophylaxis causes resistance to the last-resort antibiotic daptomycin. Nature 635, 969–977 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08095-4.

A wonkish summary is found below our signatures, but here’s the high-level version:

- Rifaximin is a non-absorbable oral antibiotic used to manage both traveler’s diarrhea and the CNS derangements that can be seen in advanced liver failure (hepatic encephalopathy).

- See this review (J Antibiotics 2014) and this Medscape summary.

- Daptomycin is a last-resort antibiotic (WHO AWaRe category of Reserve) used for Gram-positive infections, most notably serious infections due to Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species.

- It is especially valued for its activity on vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (Turnidge et al. 2020 CMI, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.027).

- FDA labeling is here and note also this FDA rationale that extends the breakpoints for Enterococcus species from E. faecalis to also include E. faecium.

- Daptomycin and rifaximin are totally different classes of antibiotics and would not be expected to have any effects on each other.

- Daptomycin is a cyclic lipopeptide that acts by binding to (and disturbing) bacterial cell membranes.

- Rifaximin is related to rifampin and acts deep within bacteria by inhibiting RpoB, an enzyme involved in RNA synthesis.

- But (and now we have the unintended consequences), a group in Australia has observed that resistance to daptomycin in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium began to emerge shortly after rifaximin was introduced in the early 2000s.

- Oddly, the mutation driving resistance was in the gene for the RpoB enzyme, so not obviously linked to the bacterial cell membrane.

- Upon deeper exploration, it turns out that the RpoB mutation indirectly leads to a change in the charge of the bacterial cell membrane in a way that reduces daptomycin binding and hence creates resistance.

Ouch! As the authors observe (emphasis is ours):

- “Coordinated global efforts are underway to preserve last-resort antimicrobials through stringent stewardship protocols, limiting the use of these critically important medicines.

- “This strategy assumes that restricted antibiotic use correlates with reduced opportunities for pathogens to develop resistance.

- “Our findings challenge this assumption, demonstrating that exposure to prophylactic rifaximin can lead to daptomycin-resistant, vancomycin-resistant E. faecium emergence without direct DAP exposure.”

Unintended consequences, indeed … biologic systems are so complex! The authors observe that the benefit/risk of rifaximin may need to be reconsidered (e.g., its use in stem cell transplantation). And as the authors finally conclude, “Our research reinforces the need for judicious use of all antibiotics, and emphasizes the delicate balance required in managing AMR while meeting clinical needs.” Agreed!

With all best wishes, Patricia & John

Patricia Bradford, PhD | Antimicrobial Development Specialists, LLC | pbradford@antimicrobialdev.com. All opinions are my own.

John H. Rex, MD | Chief Medical Officer, F2G Ltd. | Operating Partner, Advent Life Sciences. Follow me on Twitter: @JohnRex_NewAbx. See past newsletters and subscribe for the future: https://amr.solutions/blog/. All opinions are my own.

14 Mar 2024 addendum: PS: Jared Silverman, part of the team who collectively discovered and developed daptomycin, wrote in response to this newsletter saying,

- “Note that while the finding is unexpected, it is not unprecedented.

- “In our original paper on daptomycin resistance in S. aureus in 2006 (Friedman et al., https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16723576/), we reported isolating RpoB and RpoC mutations in strains undergoing serial passage in daptomycin.

- “We never fully characterized the mutations (choosing to focus on the novel membrane changes) but assumed that some changes in global transcription pattern might be influencing resistance development.

- “Similarly, in our first paper on DAP resistance in Enterococci (Palmer, et al, 2011 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21502617/), one of the strains carried a mutation in a sigma factor.

- “Again, we never characterized it but it was consistent with the same model that global transcriptional changes might facilitate resistance selection.”

Hmm! Makes one think of the comment about the most interesting statement in science being “That’s odd…”!

A deep, wonkish dive into the details:

Turner, A.M., Li, L., Monk, I.R. et al. Rifaximin prophylaxis causes resistance to the last-resort antibiotic daptomycin. Nature 635, 969–977 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08095-4.

This Australian research group performed a multi-year survey of VREfm (vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium) and noted that 19.4% of 998 VREfm isolates were also resistant to daptomycin (DAP). Some notable characteristics of these isolates:

- The isolates belonged to many different ST (sequence types) and showed no other phylogenetic clustering, suggesting that the phenotype developed independently on multiple occasions.

- There was no association of DAP-R with other mutations known to be linked to DAP resistance (mutations in the lia system regulatory genes, cls, or divIVA).

If not the usual suspects, what was the cause of DAP-R in these VREfm?

- A genome-wide association study identified 142 mutations in 73 genes significantly associated with DAP resistance. The top five were (1) an uncharacterized ABC efflux protein, (2) an uncharacterized permease protein, (3) a mannitol dehydrogenase protein, and (4, 5) genes encoding the RNA polymerase subunits RpoB (S491F mutation) and RpoC (T634K).

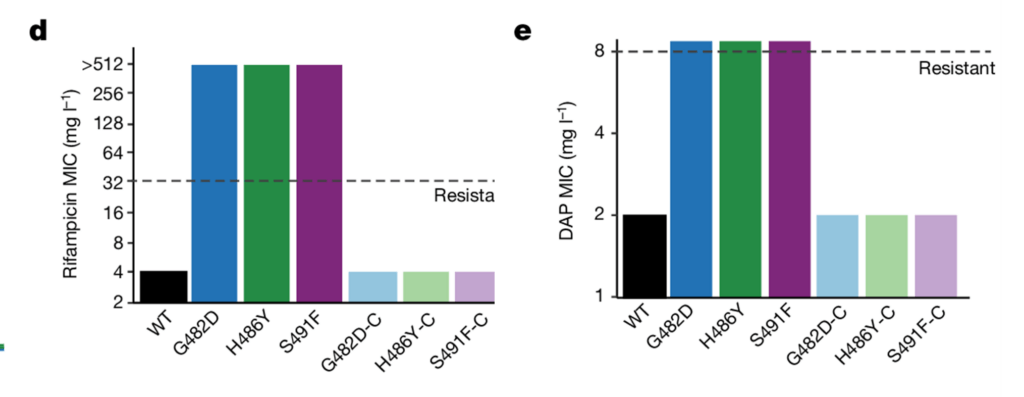

- Each of these mutations were introduced into a DAP-S isolate of VREF. Only one mutation — the S491F substitution in RpoB — increased the DAP MIC (from 2 to 8 mg/L).

- In further studies, other RpoB mutations (G482D and H486Y) increased the DAP MIC as well as the rifampicin MIC:

- Interestingly, every clinical isolate with the RpoB S491F substitution (n = 105) also contained a T634K substitution RpoC, which was found to provide fitness compensation for the mutations in RpoB.

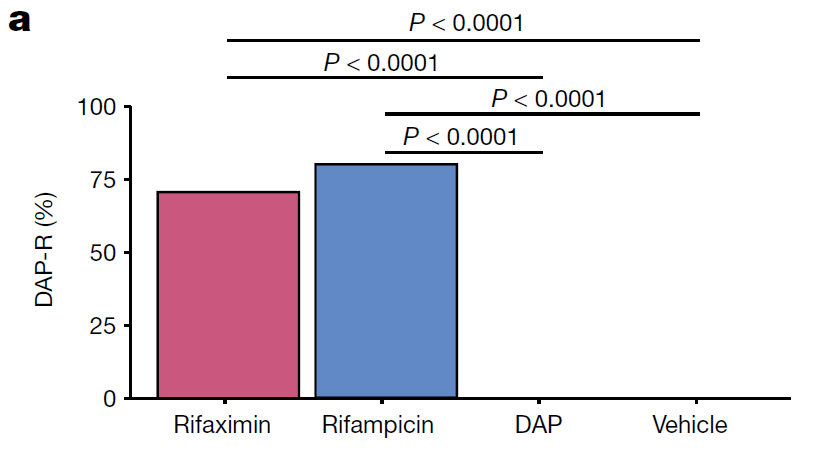

- To test the notion that treatment with rifaximin resulted in the selection of DAP-R, they used a mouse gastrointestinal colonization model with VREF and found that treatment with either rifampin or rifaximin caused de novo emergence of rpoB mutations that confer cross-resistance to DAP.

How can a mutation in RNA polymerase cause resistance to DAP? The authors used a multiomics approach to show that G482D, H486Y, and S491F RpoB substitutions led to transcriptional dysregulation of a previously uncharacterized genetic locus that they named the phenotypic resistance to DAP, or prd, operon. Upregulation of the prd operon led to VREfm cell membrane remodeling and a decreased negative cell surface charge that reduced DAP binding and, ultimately, rendered VREfm resistant to DAP.

Is this problem limited to Australia? The team searched genomic databases and found the S491F substitution was identified in VREfm genomes from 20 countries and across 21 different STs.

Why is this resistance emerging now? The authors used an evolutionary clock analysis to determine that the year of emergence for the most recent common ancestor of each cluster with S491F was around 2006, which coincides with the first clinical use of rifaximin in Australia. The expansion of the resistance has increased since 2010 when it was approved for the prevention of hepatic encephalopathy.

Yikes! This emergence of resistance was completely unexpected and unpredictable. It is a stark reminder about how the evolution of antimicrobial resistance is a continuing problem.

- The first RFP for Gr-ADI, the Gram-Negative Antibiotic Discovery Innovator, announced on 11 Feb 2025 by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF), Wellcome, and the Gates Foundation (GF) is open until 25 Mar 2025. This initial RFP seeks proposals to (i) genome-scale tools that find new chemical start points, (ii) find technologies that would select/targets leads with propensity for resistance, (iii) better understand how/why compounds penetrate the bacterial cell, and (iv) develop approaches to finding new chemical leads vs. validated targets for which there is no current Phase 3 development program. It’s clear that additional RFPs will follow … it’s quite a project! See the 11 Feb 2025 newsletter for details.

- The Trinity Challenge on Community Access to Effective Antibiotics is a £1 million innovation competition that seeks applications to answer the question: “How can data and technology improve stock control and/or reduce the use of substandard and falsified oral antibiotics for community use in low- and middle-income countries?” Applications are open at this website until 24 April 2025.

- EMA have posted a call for tenders under which they will provide up to 16m EUR for project that would “perform studies on the quality, safety and efficacy of human and veterinary medicines that would provide complementary evidence to support regulatory decision-making.” The deadline to apply is 30 April 2025. See this 17 Feb 2025 newsletter for details.

- HERA plans to post a call on 4 April 2025 in which they will call for tenders under which they will provide up to 13m EUR for development of a point-of-care diagnostic medical device that can provide antimicrobial susceptibility results on the bacteria or fungi causing an infection in humans, within one hour or less from subject sample collection, and ideally, to also allow for pathogen identification. See the 19 Feb 2025 newsletter for details.

- ENABLE-2 has continuously open calls for both its Hit-to-Lead program as well as its Hit Identification/Validation incubator. Applicants must be academics and non-profits in Europe due to restrictions from the funders. Applications are evaluated in cycles … see the website for details on current timing for reviews.

- CARB-X has open calls at intervals that span four areas: (i) Therapeutics for Gram-Negatives, (ii) Prevention for Invasive Disease, (iii) Diagnostics for Neonatal Sepsis, and (iv) Proof-Of-Concept for Diagnosing Lower-Respiratory-Tract Infections. See this 6 Mar 2024 newsletter for a discussion of the call and go here for the CARB-X webpage on the call. There are multiple opportunities to submit — see the CARB-X webpage for details.

- BARDA’s long-running BAA (Broad Agency Announcement) for medical countermeasures (MCMs) for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats, pandemic influenza, and emerging infectious diseases is now BAA-23-100-SOL-00004 and offers support for both antibacterial and antifungal agents (as well as antivirals, antitoxins, diagnostics, and more). Note especially these Areas of Interest: Area 3.1 (MDR Bacteria and Biothreat Pathogens), Area 3.2 (MDR Fungal Infections), and Area 7.2 (Antibiotic Resistance Diagnostics for Priority Bacterial Pathogens). Although prior BAAs used a rolling cycle of 4 deadlines/year, the updated BAA released 26 Sep 2023 has a 5-year application period that ends 25 Sep 2028 and is open to applicants regardless of location: BARDA seeks the best science from anywhere in the world! See also this newsletter for further comments on the BAA and its areas of interest.

- HERA Invest was launched August 2023 with €100 million to support innovative EU-based SMEs in the early and late phases of clinical trials. Part of the InvestEU program supporting sustainable investment, innovation, and job creation in Europe, HERA Invest is open for application to companies developing medical countermeasures that address one of the following cross-border health threats: (i) Pathogens with pandemic or epidemic potential, (ii) Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) threats originating from accidental or deliberate release, and (iii) Antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Non-dilutive venture loans covering up to 50% of investment costs are available. A closing date is not posted insofar as I can see — applications are accepted on a rolling basis; go here for more details.

- The AMR Action Fund is open on an ongoing basis to proposals for funding of Phase 2 / Phase 3 antibacterial therapeutics. Per its charter, the fund prioritizes investment in treatments that address a pathogen prioritized by the WHO, the CDC and/or other public health entities that: (i) are novel (e.g., absence of known cross-resistance, novel targets, new chemical classes, or new mechanisms of action); and/or (ii) have significant differentiated clinical utility (e.g., differentiated innovation that provides clinical value versus standard of care to prescribers and patients, such as safety/tolerability, oral formulation, different spectrum of activity); and (iii) reduce patient mortality. It is also expected that such agents would have the potential to strongly address the likely requirements for delinked Pull incentives such as the UK (NHS England) subscription pilot and the PASTEUR Act in the US. Submit queries to contact@amractionfund.com.

- INCATE (Incubator for Antibacterial Therapies in Europe) is an early-stage funding vehicle supporting innovation vs. drug-resistant bacterial infections. The fund provides advice, community, and non-dilutive funding (€10k in Stage I and up to €250k in Stage II) to support early-stage ventures in creating the evidence and building the team needed to get next-level funding. Details and contacts on their website (https://www.incate.net/).

- These things aren’t sources of funds but would help you develop funding applications

- The Global AMR R&D Hub’s dynamic dashboard (link) summarizes the global clinical development pipeline, incentives for AMR R&D, and investors/investments in AMR R&D.

- Diagnostic developers would find valuable guidance in this 6-part series on in vitro diagnostic (IVD) development. Sponsored by CARB-X, C-CAMP, and FIND, it pulls together real-life insights into a succinct set of tutorials.

- In addition to the lists provided by the Global AMR R&D Hub, you might also be interested in my most current lists of R&D incentives (link) and priority pathogens (link).

John’s Top Recurring Meetings

Virtual meetings are easy to attend, but regular attendance at annual in-person events is the key to building your network and gaining deeper insight. My personal favorites for such in-person meetings are below. Of particular value for developers are the AMR Conference and the ASM-ESCMID conference. Hope to see you there!

- 11-15 April 2025 (Vienna, Austria): ESCMID Global 2025, the annual meeting of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Go here for details.

- [UPDATED] 30 Sep-2 Oct 2025 GAMRIC, the Global AMR Innovators Conference (Washington, DC). Formerly the ESCMID-ASM Joint Conference on Drug Development for AMR, this meeting series is being continued under the joint sponsorship of CARB-X, ESCMID, BEAM, GARDP, LifeArc, WHO, and AMR.Solutions. You can’t yet register for this meeting but please mark your calendar now. The ongoing series is expected to continue that successful format of prior meetings with a (mostly) single-track meeting and you can also go here to see details of the outstanding 2024 meeting.

- 19-22 Oct 2025 (Georgia, USA): IDWeek 2025, the annual meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Details pending; go here for the general meeting website.

- [UPDATED] 3-4 Mar 2026 (Basel, Switzerland): The 10th AMR Conference. Sponsored by the BEAM Alliance, the 9th AMR Conference has just concluded and it’s again been an excellent meeting! Please mark your calendar for next year. You can’t register yet, but details will appear here!

Upcoming meetings of interest to the AMR community:

- [NEW] 28 Mar 2025 (virtual, 10.00-11.15a ET): GARDP-sponsored webinar entitled “Cefiderocol access project: Where are we now?”. This will be an update on GARDP’s work to enable access via lower-cost manufacturing in India (see the 25 Sep 2023 newsletter for background). Go here to register!

- [NEW] 3 Apr 2025 (virtual, 10.00-11.15a ET): GARDP-sponsored webinar entitled “Charting new frontiers in artificial intelligence for antibiotic design.” This is a fascinating area … as background, you might enjoy reading our 5-part series on AI-based discovery that began on 21 Feb 2020. Go here to register!

- 11-15 April 2025 (Vienna, Austria): ESCMID Global 2025, the annual meeting of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. See Recurring Meetings list, above.

- During ESCMID, mark your calendar for the Science Policy forum during which we’ll have follow-up from UNGA 2024 (11 April, 3-8p CEST) and Pipeline Monday (14 April) during which we’ll have a variety of sessions on the antimicrobial pipeline. See also the 13 Feb 2025 newsletter for details and commentary.

- I’ve also learned of a 14 April (12.15-1.15p, Hall 8) symposium on mechanisms to expand access to antibiotics. To find this one, you have to go the general program and navigate to Hall 8 at 12.15p. Awkward, but a direct link is not possible due the design of the ESCMID webpage.

- [NEW] 30 Apr 2025 (virtual, 10-5.15p ET): Presented by Sepsis Alliance, the Sepsis Alliance AMR Conference is 1-day virtual discussion of AMR- and sepsis-focused diagnostics, therapeutics, and advocacy. Go here for details and to register.

- 30 June – 1 July (in person and virtual, Grand Hyatt, Washington DC): BARDA Industry Days 2025 (BID2025) with the theme “Enhancing Health Security With a Sustainable Future.” This is a major annual opportunity to interact with BARDA and ASPR teams and thereby identify potential areas of collaboration in the field of MCM (medical countermeasure) research and development. Go here for details.

- 19-22 Oct 2025 (Georgia, USA): IDWeek 2025, the annual meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society

- 11-15 April 2025 (Vienna, Austria): ESCMID Global 2025. See list of Top Recurring meetings, above.

- 30 June-1 July 2025 (virtual and in Washington, DC): BID2025: BARDA Industry Days — Enhancing Health Security With a Sustainable Future. BID provides the opportunity to discuss U.S. government medical countermeasure (MCM) priorities, provide the private sector an informal opportunity to interact with BARDA and ASPR teams, and identify potential areas of collaboration in the field of MCM research and development. Go here for details.

- 30 Sep-2 Oct 2025 GAMRIC, the Global AMR Innovators Conference (Washington, DC; formerly the ESCMID-ASM Joint Conference on Drug Development for AMR). See list of Top Recurring meetings, above..

- 19-22 Oct 2025 (Georgia, USA): IDWeek 2025. See list of Top Recurring meetings, above.

- 11-19 Oct 2025 (Annecy, France, residential in-person program): ICARe (Interdisciplinary Course on Antibiotics and Resistance) … and 2025 will be the 9th year for this program. Patrice Courvalin orchestrates content with the support of an all-star scientific committee and faculty. The resulting soup-to-nuts training covers all aspects of antimicrobials, is very intense, and routinely gets rave reviews! Seating is limited, so mark your calendars now if you are interested. Applications should open ~March 2025 — go here for more details.

- 3-4 Mar 2026 (Basel, Switzerland): The 10th AMR Conference sponsored by the BEAM Alliance. See list of Top Recurring meetings, above.

- OpenWHO: “Antimicrobial Resistance in the environment: key concepts and interventions.” Per the webpage for the course, it will teach you “…why addressing AMR in the environment is essential and gain insights into how action can be taken to prevent and control AMR in the environment at the national level.” This course builds on WHO’s 2024 Guidance on wastewater and solid waste management for manufacturing of antibiotics. For further reading, see also the 25 Sep 2023 newsletter entitled “Manufacturing underpins both access and stewardship: Cefiderocol as a case study” and the 28 Jan 2024 newsletter entitled “EMA Concept Paper: Guidance on manufacturing of phage products”.